By: Dr. Delphin R. Ntanyoma

Introduction

The Banyamulenge are a Congolese Tutsi minority community primarily living in the Hauts-Plateaux region of South Kivu, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Despite being there for centuries, they continue to face persecution, displacement, and violence. Deep-rooted ethnic hostility, fueled by political manipulation and regional conflicts, has led to widespread misconceptions that portray them as foreign “invaders” or outsiders linked to Rwanda, rather than as an essential part of the Congolese nation. For many decades, the Banyamulenge’s contested status has remained a key driver of violence targeting members of this community. In an emerging field of study, I apply the slow genocide perspective to analyze different methods used to target the Banyamulenge. The persecution and discrimination against the Banyamulenge aim to eliminate or remove them.

However, the Banyamulenge’s specific plight and experiences are frozen mainly in the complex violent settings that have characterised the DRC and, more broadly, the African Great Lakes region. Currently, their plight is compounded by the resurgence of the rebel group, Mouvement du Mars (M23), which resurged in November 2021 in North Kivu (DRC). M23 is an offspring of an armed group that signed a peace agreement with the Congolese government in 2009. With an insurgent approach, M23 claims, among other things, to defend and protect Congolese Tutsi’s rights. Subsequently, the resurgence of the M23 has come to dominate socio-security and political analysis at local, national, and regional levels. The 2021 resurgence is even used to justify attacks against the Banyamulenge in Uvira and its surrounding localities.

Taking, for example, violence against the Banyamulenge began in 2017, I see such violence having less to do with the 2021 resurgence of M23 or any expressed sympathy toward this rebel group. The resurgence of the M23 offers a narrow picture and may mislead policy prospects. This experience shows that any event or incident can be used to justify attacks against the Banyamulenge. From 2017 onwards, local and foreign armed combatants destroyed almost all of the Banyamulenge homeland, and armed combatants used different events to justify their attacks. More specifically, attacks occurred while the Banyamulenge political and military elite opposed the emergence of the M23 (2012-2013) and distanced themselves from the Rwandan-backed rebellions in the eastern DRC. 1

How events shape narratives

In early September 2025, a military General affiliated with the Banyamulenge within the Congolese armed forces, known as the Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC), was appointed in Uvira, one of the cities in South Kivu province. General Olivier Gasita, a member of the Banyamulenge community, was appointed as the Commander in charge of operations and intelligence. From early 2025, Uvira served as the headquarters of the South Kivu provincial institutions following the rebel group, Mouvement du M23 Mars (M23), capturing Bukavu. Uvira is now the capital city of South Kivu for areas under the control of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) government.

The appointment of Olivier Gasita triggered fierce contestations from commanders of local militias and armed groups. The local militias and armed groups, under the banner of Wazalendo (patriots in Kiswahili) were integrated into the FARDC as Army and Defense Reserve (Reserve d’Armée et de défense: RAD) to combat the resurgence of the M23.

In Uvira, several militias and armed groups’ commanders openly claimed that they do not want to see an FARDC general whose physical appearance is like a “Rwandan, Tutsi or M23 sympathiser.”2 Local claims referred to his physical appearances, calling him “Rwandan” or Tutsi, as reasons the General is not accepted in Uvira. Later, local populations and members of civil society organisations joined the contestation and organised demonstrations in support of the armed groups’ combatants’ claims. On September 8, 2025, Uvira’s residents and civil society organisations joined the protest to contest General Olivier Gasita. The discourse shifted to blame Olivier Gasita for plotting to let rebels capture Bukavu. Singled out, this was another way to exploit the occupation of Bukavu by rebel groups to justify this contestation.

There is evidence that General Olivier Gasita was clearly targeted because of his ethnic affiliation. While General Olivier Gasita’s background suggests otherwise, demonstrators claimed he sympathises with the M23. And this persisted despite FARDC’s hierarchy reassuring the public of his loyalty to the Congolese armed forces. Some media sources confirm that General Olivier Gasita has not been performing his duties in Uvira, leading to the belief that he has been removed from the position.

During this contestation period, Banyamulenge civilians who live in Uvira or who travelled there were specifically targeted and attacked. On September 15, 2025, Human Rights Watch reported on these incidents that:

Concerns over the protection of civilians in Uvira were heightened by tensions over the appointment of a new army commander. Wazalendo fighters have harassed, threatened, abducted, and restricted access to services for members of the Banyamulenge community in Uvira, who are South Kivu-based Congolese Tutsis, accusing them of supporting the M23.

In May 2025, Human Rights Watch reported that “Many Wazalendo abuses have targeted the Banyamulenge (plural for Munyamulenge, referring mainly to South Kivu-based Congolese Tutsis), who have long been accused of being M23 supporters.” Whilst “being supporters of M23” is an allegation used to justify attacks against Banyamulenge, General Olivier Gasita is known to oppose the influence of the Rwanda Defense Forces (RDF) in the DRC and on Banyamulenge, and has never publicly sympathised with the M23. What is obvious, as it is in other similar settings, is that local militias and armed combatants use any pretext to justify their deep-seated ideology against those they perceive as “invaders”.

Background of the Banyamulenge persecution

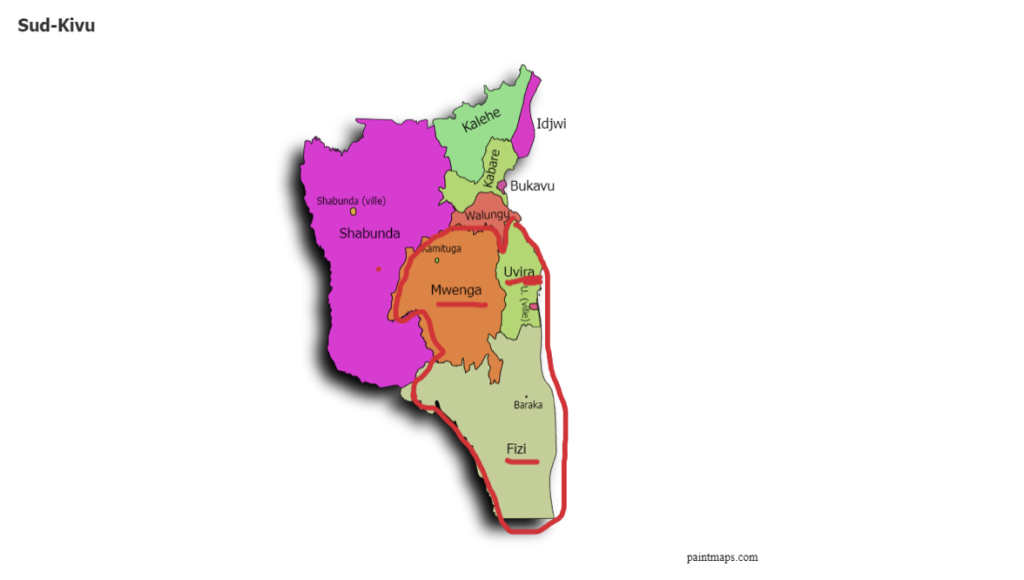

The Banyamulenge have lived in the DRC for three to four centuries. Their homeland is located in South Kivu province, specifically in the Fizi, Mwenga, and Uvira territories. In the 1970s, some Banyamulenge families moved to Katanga, Vyura localities (currently Tanganyika province), where 20,000 individuals were chased away in 1998 by the Congolese state military. South Kivu is one of the eastern DRC’s conflict-prone regions, along with North Kivu and Ituri.

Note: The Eastern DRC map. South Kivu, North Kivu, and Ituri provinces (credit: map uploaded by Nidhi Nagabhatla).

Despite a long settlement history, the Banyamulenge are fiercely contested by armed militias affiliated with neighbouring ethnic communities, political figures, and members of Congolese civil society organisations. They believe and publicly express that Banyamulenge are not “real Congolese”. Following misrepresentations and political manipulation, most local populations perceive them as “strangers and foreigners” in their own country, where they have lived for centuries.

Note: The Banyamulenge live in the three territories of South Kivu (Mwenga, Uvira, and Fizi). Credit: paintmaps.com

During the colonial period, the Banyamulenge were miscategorised as “newcomers” in what became the DRC. Scholars and researchers agree that culture, language, and physical appearance played a role in this misclassification. Colonial racialised classifications have set a tone for the persistent discrimination and persecution of the Banyamulenge.

Since independence in 1960, politicians have manipulated their constituencies, provided support to militias, and regularly engaged in dehumanising campaigns for political and electoral reasons. From the 1970s to the 1990s, the Banyamulenge were denied the right to vote, their citizenship stripped, and the Congolese state resolved to expel them in 1995.

In the 1996 to 1998 wars, the Banyamulenge and some foreign nationals were systematically killed across the DRC based on their “physical characteristics,” and this followed public speeches of government officials, ministers, and military generals who called for the elimination of “scums and vermin”. In Burundi in 2004, the Banyamulenge were deliberately murdered, whilst supposedly under UNHCR protection.

More recently, politicians have resorted to online hate speech and mobilisation to create resentment against the Banyamulenge. Political figures, military soldiers, and members of civil society organisations have openly claimed that they will use their power to expel all the Banyamulenge from the DRC.

For more than three decades now, the DRC has experienced wars and violent conflicts that have claimed millions of deaths. In a context characterised by decades of violent conflicts, being portrayed as “foreigners and invaders” in their own country makes members of the Banyamulenge more vulnerable compared to other local populations. Their plight and unique experiences are highly overshadowed by the complexity of violence in the Eastern DRC, the African Great Lakes regional confrontations that oppose countries and armies.

The 2025 Banyamulenge situation

In January and February 2025, the M23 defeated the FARDC and its allies, occupying Goma and Bukavu, the capitals of North and South Kivu provinces, respectively. Some individuals and Banyamulenge groups publicly joined the M23. This development justifies the blockade that has been in place since 2017 and was reinforced in 2019. The Congolese armed forces and local militias claim that the blockade is intended to fight against M23 and its allies (see the section below). From early 2025 onwards, there is no single route from which one can come in or get out of this tiny area where thousands of civilians are sheltered.

Consequently, due to this persistent armed siege imposed on Banyamulenge civilians by the Congolese army and local militias, in Minembwe (for instance), the situation of the local population is extremely uncertain. Minembwe is an area sheltering thousands of civilians who have been deprived of their economic and social assets. They struggle to find basic products on local markets. For instance, the price of 1 kg of sugar is approximately $10, that of salt is $11, while that of soap is $10. The price increase is approximately 400% higher than in late 2024. In addition to their extraordinarily high prices, these basic products are very rare as they can only be obtained at a 50-60 km walk (one way). Such a long walking distance is associated with high risks of being killed or attacked by armed combatants.

Because of such an imposed siege, it is largely impossible to help the casualties and wounded people because health facilities are running out of stock in Minembwe. There is no single transport route (no road, no airlift…) through which casualties can be transported (evacuated) outside of Minembwe.From early 2025 onwards, existing transport routes were blocked entirely, and telecommunications facilities were destroyed; all means of sending financial support to relatives and families were also blocked. See the map below:

Note: The picture shows the map of Minembwe (Fizi territory/ South Kivu), where many Banyamulenge are now besieged (less than 10 km2)

On the 30th of June 2025, an airplane was destroyed by a drone in Minembwe. Some sources have claimed the airplane was on a humanitarian mission. While it’s yet unclear if the aircraft was a humanitarian one, the destruction endangers efforts to provide humanitarian assistance to civilians. Health facilities in Minembwe are overwhelmed. Many injuries with life-threatening wounds are hardly treated because health facilities cannot get basic medication and equipment supplies.

On top of that, local militias previously known as MaiMai and Biloze-Bishambuke, affiliated to Banyamulenge’s neighbouring ethnic groups, have received guns and ammunition from the DRC government and the army (FARDC) to oppose the rebel group M23 and its ally, the Rwanda Defense Forces (RDF). These local militias and combatants, currently known as Wazalendo (patriots), are integrated into the Congolese armed forces as reserve forces.

These guns are now used to attack Banyamulenge civilians. Local militias in South Kivu have found an excuse: “Twirwaneho”, the Banyamulenge-affiliated self/armed group has officially joined M23/AFC (Alliance Fleuve Congo). The fact that Twirwaneho has joined M23/AFC justifies attacks against the Banyamulenge civilians. Such a volatile and uncertain context is hugely affecting the Banyamulenge civilians who have endured impoverishment and extreme violence for the last 8 years.

2017 onwards: Banyamulenge’s experience —slow genocide.

Since 2017, the socio-security context in South Kivu has drastically deteriorated as DRC, Rwanda, and Burundi have fought a proxy (direct) war. Countless militias received ammunition and guns from belligerents. It has been documented that Rwanda’s proxy, Burundian Red-Tabara, coalesced with local militias to attack the Banyamulenge. At the same time, Burundi supported Rwandan rebel groups that intended to attack Rwanda.

The coalition of local militias and Burundian rebels supported by the Congolese armed forces has destroyed the Banyamulenge’s homeland. This was another wave of violence that targeted members of the Banyamulenge community in the DRC on the basis that they do not deserve to live in this country.

From 2017 to the present, local armed combatants, in collaboration with Burundian rebels, burnt to ashes Banyamulenge’s settlements (villages), estimated between 350 and 400. Food stocks and crops were systematically destroyed. The Banyamulenge who lived in these localities were forced to flee either outside of DRC or live in a few internally displaced people (IDP) sites (approximately four).

Banyamulenge’s IDP sites had been subjected to systematic and coordinated military attacks, leading to an imposed siege and starvation. The Banyamulenge have been denied access to their farmlands within a distance of 2 to 3 kilometres. The only way to travel from some of these enclaves to other parts of the world is through expensive and irregular airlifts. The siege has constantly threatened people’s existence.

Nearly 400,000 Banyamulenge cattle were pillaged or killed during these attacks. Cattle are the Banyamulenge’s main source of income and livelihood. Cattle-looting had impoverished almost all members of the Banyamulenge community while serving as a resource to reward and increase the militias’ military capabilities. Ways the Banyamulenge were targeted by local and foreign militias supported by the Congolese armed forces are summarised in the Conversation.

These attacks have physically, socially, and psychologically affected members of the Banyamulenge, and many have fled to the DRC’s neighbouring countries. However, their unique experience is frozen in the African Great Lakes’ regional conflicts, and more attention is paid to countries’ claims.

Conclusion

‘Violence in the Eastern DRC is complex, local, regional, and has ramifications beyond. The 2017 destruction of the Banyamulenge homeland was partly triggered and sparked by proxy wars between Rwanda and Burundi following the 2015 failed coup in Burundi and the 2016 delayed general elections in the DRC. Rwanda, Burundi, and the DRC supported foreign militias fighting on their behalf, and these militias have since allied with local armed groups. The current context in 2025 is reflecting again what happened back in 2017. The Banyamulenge and other minorities are targeted by forms of violence that intend to get rid of them in the DRC. These forms of violence use incidents and events to advance their agenda to wipe out minorities.

Wars and conflicts are borderless in the digital era. The Banyamulenge are extremely targeted by online campaigns, and hate speech mostly proliferates by influential politicians and activists (social media users) who rely on the facilities offered by social media platforms’ accessibility. While armed combatants resort to guns to kill and destroy, social media platform users continue to mobilise for the elimination of those perceived as “invaders”. Social media platforms (Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube) contribute to propagating hate speech, misinformation against ethnic minorities, and mobilise resources to support perpetrators of violence.

Efforts to stabilise the eastern DRC overlook the security conditions of minorities. They tend to pay attention to claims raised by state actors (countries and rebel groups) and largely ignore the plight of ethnic communities, sometimes located in the “no man’s land” and in the crossfire of a regional competition. For instance, the United States under the Trump administration and the Qatari government are working to secure peace agreements between the DRC and Rwanda, as well as between the DRC and the M23. It appears that the Banyamulenge’s inhumane situation is again being overlooked. Africa-led initiatives, including the African Union (AU), the East African Community (EAC), and the Southern African Development Community (SADC), have focused on addressing countries’ claims.

The international community and human rights organisations need to pay attention to such hatred campaigns and ensure that individuals linked to such forms of violence are held accountable. This is an urgent situation that requires specific attention from the international community and organisations standing up against genocide, mass atrocities, and violence targeting minorities, particularly in South Kivu and in Ituri.

Footnotes

1 Though documented by local sources and the United Nations Group of Experts, Rwanda has dismissed providing support to the rebels in the eastern DRC.

2 See also this video of a well-known militia’s commander, Amuli Yakutumba who is sanctioned by the United Nations: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0yh2nI2sLQs