I am a Research Analyst at the International Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies (a division of the Zoryan Institute) and I want to address the recent social outcry pertaining to gender-based harassment, and sexual gender-based violence (SGBV). SGBV has been used as a tool and has been a result of conflict. SGBV in peace-time escalated to become a tool of ethnic, cultural, and religious cleansing, as we reminisce in Rwanda, Bosnia, and Kosovo. It is perpetrated by mindsets supporting gender inequality, an inequality that has been shaped by institutionalized and systemic patriarchal power relations. As a new Research Coordinator, I wanted to highlight that ignorance and indifference remain key factors perpetrating escalation of violence. Indifference fosters impunity, which then makes things difficult for transitional justice and reconciliation. Indifference is created by the pre-emptive lack of awareness and education of boys, girls, men, otherwise self-identified, and women.

In order to break away from patriarchal norms and eradicate the indifference to gender inequalities supporting SGBV escalation, education is a must. By that I do not only mean formal education in the classroom, nor workshops at work. I mean experiential knowledge and exposure to the voices of the most vulnerable groups, in a joint grassroots and top-down perspective. Gendered stereotypes, sexual stigma and shame, and varying cultural views on gendered attitudes ought to be addressed through education in order to guarantee such atrocities do not happen again.

While not a visible zone of conflict, Canada is no stranger to such crimes. Canadian views on gender relations are shaped by its colonial legacy, the cultural genocide, the gender equality gap, and the diversity of experiences inhabiting what constitutes Canada today. And we will see that while Canada has been making efforts to tackle gender issues, the situation has been stepping back.

As an individual at a crossroad between the French and North American cultures, my experience of what constitutes gender equality in séduction and sexual relations is multiple. I have grown more conscious of the subtle legacy of religious and cultural oppression of women’s sexual liberty and agency. As a Belgian-Quebecer woman in Ontario, I can’t help but witness the clear gap in sexual education amongst young men and women throughout Canada (Ontario’s sex ed on consent and sexual abuse is now Grade 7). The change in attitudes towards women’s sexuality and gender relations has been a hypocritical journey. This journey reflects the secularization and diversification of society. In Canada, many individuals have to navigate amongst diverse cultural and religious identities. But Canada is also where certain groups remain more vulnerable due to a myriad of intertwining historical factors, supporting a cycle of impunity towards gender-based harassment. In fact, according to various studies, the most vulnerable demographics remain self-identified LGBTQ, young women (15-24), and indigenous women.

Acknowledging its position of historical privilege and the legacy of its colonial past, the Canadian government has been making efforts to foster the need to document sexually gender-based violence towards indigenous women and girls, to represent women in politics, and include a Gender Based Analysis (GBA+) and gender mainstreaming mechanisms at the policy-level.

Despite these efforts, a 2017 study conducted by Statistics Canada shows that the rate of reported sexual assaults in 2014 equated numbers collected ten years ago (2004). Sexual assault remains one of the most unreported crimes due to shame, guilt, stigmas of sexual victimization, and the normalization of inappropriate, or unwanted, gender-based sexual behaviours. From the reported assaults, 52% were committed by a friend, acquaintance or neighbour. Furthermore, the stigmas and lack of training of RCMP officers have hindered their relationship with vulnerable groups, key factors in reporting mechanisms.

Such numbers show that there is a clear need for more top-down educational efforts. But the fact that acquaintances make most of the offenders list, calls for joint grassroots educational initiatives. Grassroots examples explained below are creating a change in attitudes at the community and household level, to make for governmental efforts’ shortenings.

In that stream, indigenous grassroots organizations in Canada have been working hard to provide a safe space for survivors to share their stories, and change attitudes over sexual stigmatization and shame. Indigenous programs such as the Moose Hide Campaign, are providing the grassroots awareness tools for indigenous and non-indigenous men. Such tools are meant to support women and children against violence in and out of indigenous communities. At this time, they have inspired local, governmental, and academic organizations to conduct their own local campaign, amounting to 750,000 stakeholders.

It is worth noting that the Canadian grassroots experience has also been transcending national borders. This next successful example inspires on how the use of human rights law education by a Kenyan survivor, Mercy Chidi and a Canadian NGO leader, Fiona Sampson, has been making a change for girls in Kenya.

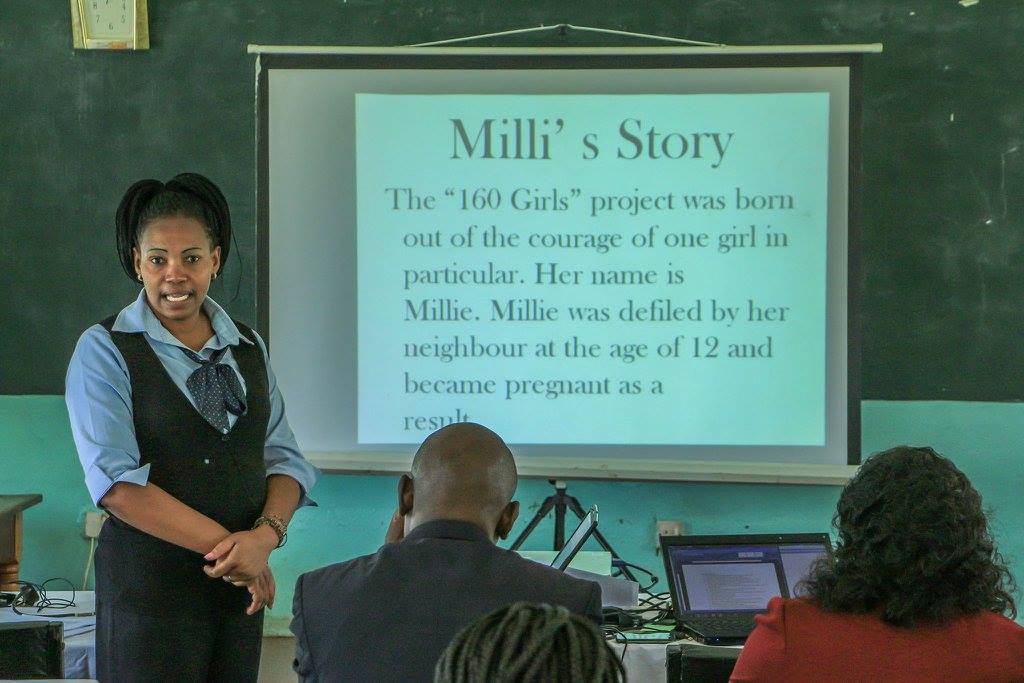

These two strong women partnered with 160 Kenyan girls under the 160girls initiative, which became a precedent-setting court case, in an attempt to change the way a country looks at girls. In 2013, lawyers from Canada and Kenya helped 160 girls from Meru sue the Kenyan government for failing to protect them against rape. The decision resulted in the implementation of a compulsory pilot training of Kenyan officers and the implementation of the Kenya Public Legal Education Plan. A sustainable school workshop program was implemented under the name of “Justice Clubs”, for boys and girls to learn about the law on defilement, the police and the community role, and discuss how to stop rape and violence.

By having police officers in workshops to talk about means of reporting and trust, such a program has changed the relationship of the youth with the police. In 2016, 2400 police officers (40% women) were trained in Kenya with local trainers. Today, trained officers have scored much higher in arresting suspects of defilement: from 0/10 to 8.4/10. (2017 Interim evaluation)

The 160girls initiative is a long-term project, but most importantly, it is about building trust, creating knowledge, and accountability to empower boys and girls. Such successful examples show that there are many possibilities for grassroots ways of enthusing change and countering legal impunity. It calls for more educational opportunities across the country to include men and boys in the narrative, and address the systemic attitudes sanctioning gender-based violence.

As we have seen, the Canadian government has been failing to address SGBV stigmas through its top-down gender mainstreaming efforts. Grassroots educational programs have been showing fruitful results at the community and judicial level at home and abroad. These successful stories depend on a joint effort with government. A joint top-down and grassroots perspective to education is thus needed in order to change the way a country looks at gender relations at all levels.

Mégane Visette is a Research Analyst at the International Institute for Genocide and Human Rights studies (a division of the Zoryan Institute).

Photo : “Women’s March in Istanbul” (2017), by Özge Sebzeci via flickr. Licensed under CC2.0

From top to bottom:

Source: “Gender & Genocide studies” (2017) courtesy of Megan Reid during GHRUP program. All rights reserved.

Source: “Moose Hide campaign stands up against violence” (2015) by Province of British Columbia Photo Stream via flickr. Licensed under CC2.0

Source: “Public Legal Education Chiefs workshop – Meru County” (2016) by The Equality Effect via Facebook