On April 7th, at Toronto’s swanky but traditional Granite Club, guests celebrated the Zoryan Institute’s 35th Anniversary Gala & World Premiere of an Armenian Journey II: Vindication. The tone of the party was light and easy-going, but underneath jovial appearances there boiled an important political statement. While the Zoryan Institute is not a human rights or activism group, it would be odd to say that it is entirely apolitical. Through scholarship the Institute has made an important political statement on the universal realities of human rights and genocide. I am sure most would agree that education and the sharing of knowledge is a form of activism itself. But the Institute does not support a specific academic cause, even if it is focused to some extent on the Armenian Genocide, its context is a universal one. Producer and actress Arsinée Khanjian’s introductory speech perfectly encapsulated the Institute’s universal mission, while also including delicious morsels from her experiences with some of the Institute’s founders. It was a poignant way to begin the celebrations.

There was champagne. Canapés were served. Guests mingled and twirled around tables decorated with fine china and fresh flower arrangements. But the night was so much more than hedonistic hobnobbing. Ted Bogosian would premiere the second part of his acclaimed documentary on the Armenian genocide, featuring the remarkable genocide survivor Miriam Davis. It was, in fact, the first documentary on this subject to be aired on television. Guests focused their attention on projected screens on either side of the hall’s walls. We were silent in anticipation. We see an older Bogosian fade into his younger self—he narrates how recent discoveries in the history of the Armenian genocide has provided Armenians all over the world vindication. The main protagonist Miriam Davis wears cat-shaped glasses and smokes cigarettes as she weaves her story as a survivor in a seamless manner. I cannot look away. I want to hear more. It was incredibly touching to learn that the stories Mrs. Davis had shared in the first documentary were all proven to be true by the research of various Zoryan Institute scholars, including Wolfgang Gust and Vahakn Dadrian. She was not just weaving stories—Mrs. Davis had perfect recollection of the tragedies that occurred in her youth. She spoke to the events surrounding her mother’s execution in such a detailed manner. Trauma is never forgotten. It burns an image in our mind’s eye. To challenge Mrs. Davis would be to challenge the very nature of trauma and its impact on the human psyche (and of course, the supporting historical German and Turkish documents).

An important element of director Bogosian’s documentary included a scene where Mrs. Davis’ daughter spoke to her hesitancy in believing her mother’s stories. She noted that when they were actually able to travel to the locations where the atrocities occurred, she could not deny what her mother had told her for many years before. A scene showing Mrs. Davis by the Euphrates river—where her mother had been executed by drowning—moved me deeply. Seeing her drop flowers she collected into the water was a symbol of Mrs. Davis’ healing process. A symbol of her own personal search for vindication.

It is clear that Bogosian’s theme for his second documentary was drawn from Mrs. Davis’ experiences in the first film. If Mrs. Davis could finally be vindicated, so could the millions of Armenians in the world who are waiting for recognition that what happened to their parents, grand-parents, and great-grand parents actually happened. I felt in that moment that all those who experienced trauma in any context could understand the importance of being told that what happened to them was not only real, but wrong. Vindication. A standing ovation.

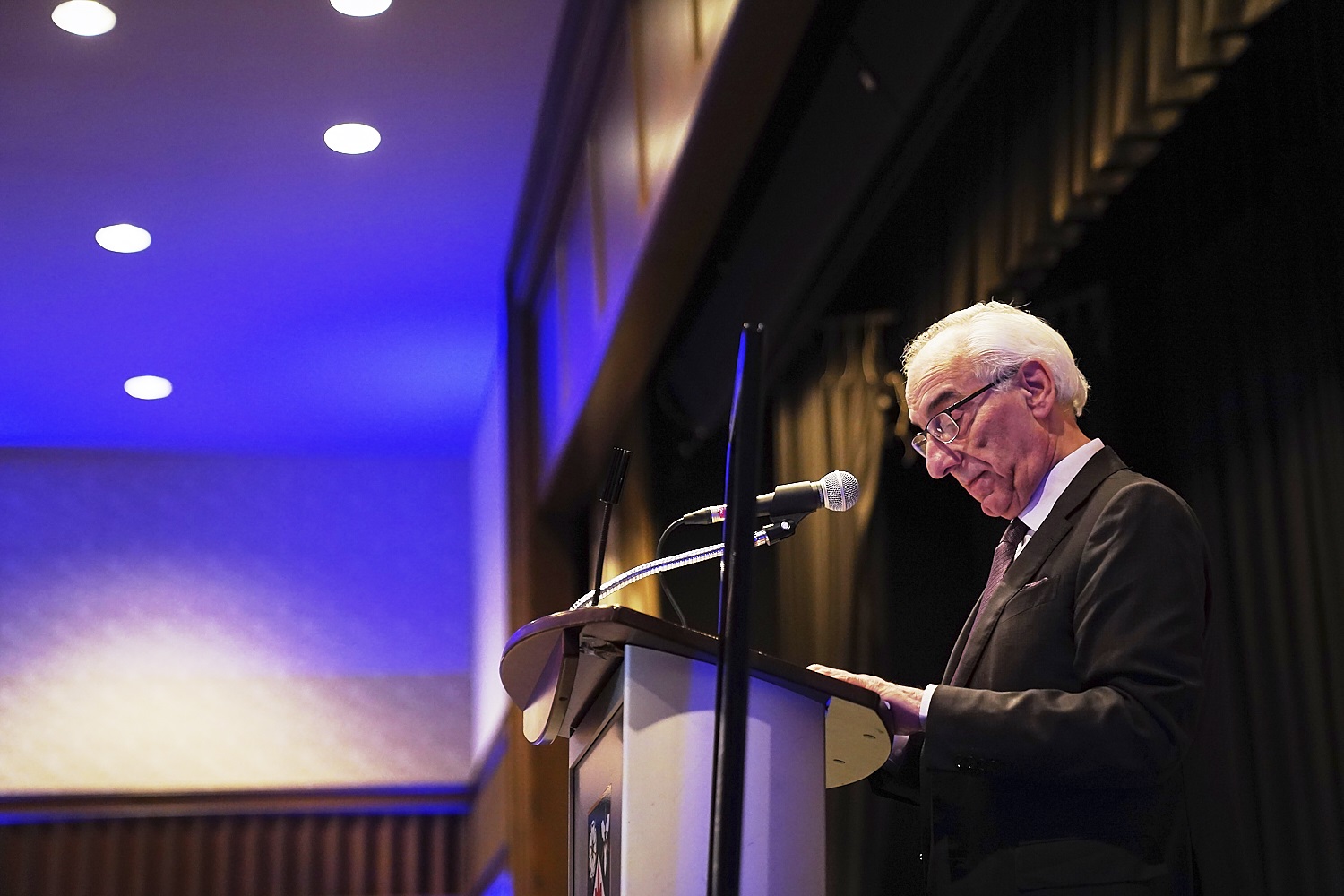

After the documentary ended, Kourken (Greg) Sarkissian, one of the founders of the Zoryan Institute, shared with us a few words of thanks to those who contributed to the organization in the past 35 years. An entrepreneur in his day job, so to speak, Kourken and his colleagues managed to elevate the name Zoryan to international renown through the establishment of peer-reviewed journals, book publications, an oral history project, etc. After a few words on his hopes about the future of the Institute, he welcomed Rakel Dink to the stage, widow of the Turkish born journalist Hrant Dink (who was executed for speaking out on the Armenian genocide). Rakel personally gave plaques for the awards of recognition to Arsinée Khanjian, Lena Sarkissian, Shake Toukmanian, Joyce Apsel, George Shirinian, Levon Chorbajian, Vahakn Dadrian, Varouj Aivazian, Henry Theriault, Herbert Hirsch, and Roger Smith, who, as Chairman of the Institute’s Academic Board, has contributed to the Institute for over 30 years. I knew very little about Mrs. Dink, but noticed immediately the way people treated her—with respect and great dignity. Mrs. Dink, along with her late husband, were activists in the fullest sense of the word (a word that is used too easily nowadays). To have her present the plaques to the award winners was a testimony to the kind of work Zoryan achieved since its inception. I was proud, even though I am not Armenian.

The award ceremony was followed by a speech by Varouj Aivazian. For anyone interested in academia, it was definitely a star studded night. It is one thing to invite important guests when celebrating such a momentous occasion, but the Zoryan Institute did something more special—it invited guests who were genuinely engaged and interested in the Institute’s causes. Aivazian, as a board member and Armenian, added another experiential layer to an evening full of fascinating insights on the organization’s growth until now.

We continued to enjoy food and drink. We enjoyed the dulcet tones of the piano player, Raffi Bedrosyan, who entranced us with traditional Armenian folk music. During the intermission, we browsed the many fanciful items for the silent auction, which would support the Institute in full. After such pleasant entertainment and the impact of inspirational speeches, I hoped the Institute would be successful in its fundraising.

One of the highlight’s of the evening was Atom Egoyan’s keynote speech. I knew of his work as a movie buff of sorts. As Kourken said, the real dessert would be Egoyan’s speech. And it was. He spoke eloquently about the Zoryan Institute as a source of inspiration in his life. As a proud Armenian and more importantly, a citizen of the world, he drew a picture of what he would like to see for society. He showed concern for current issues that we must address collectively. There was nothing left unsaid when he was done. From his modest beginnings as an aspiring diplomat at university in Toronto to an established filmmaker and leader among the Zoryan community, Egoyan was able to tell us all why the Institute and its contributors are worthy of such a grand night.

The evening wrapped up in the lackadaisical way evenings do when everyone is a bit tired (and perhaps a bit drunk and a touch heavy with food). But the lingering emotion that stayed with most of us that evening was anything but lackadaisical… we felt empowered. I left the Gala hall wanting to do more, see more, learn more… There was so much I didn’t know and the knowledge I could access was just at my fingertips thanks to the Zoryan Institute. I have already made my order of Taner Akçam’s A Shameful Act (published by the Zoryan Institute). If the Zoryan Institute’s 35th Anniversary Gala wanted to inspire us to contribute in any way we can, it did so with great success.