Written by: Anastasia Leshchyshyn

Research Associate, Holodomor Research and Education Consortium

2019 Graduate of Zoryan Institute’s Genocide and Human Rights University Program at UofT

Article

The Man-Made Famine 1932-1933

25 Nov 2019

Article

25 Nov 2019

Written by: Anastasia Leshchyshyn

Research Associate, Holodomor Research and Education Consortium

2019 Graduate of Zoryan Institute’s Genocide and Human Rights University Program at UofT

In 1932-33, a catastrophic man-made famine raged in Soviet Ukraine. Millions died in this famine – now called the Holodomor – which in Ukrainian means “death by starvation.” On November 24, Holodomor Memorial Day, the victims of the famine are commemorated, and Holodomor awareness events are held worldwide. We also take this opportunity to reflect on the significant strides that have been made in Holodomor studies in recent years, and to consider new avenues for both research and advocacy.

The Holodomor began with the forcible removal of peasants from their land onto state collective farms. Impossibly high grain requisitions followed, which demanded more than the peasant farmers had to give. Though they were aware that starvation was spreading, the authorities increased grain quotas and sent troops house to house to uncover and seize remaining foodstuffs.

Ukraine’s borders were closed, preventing the starving from seeking food elsewhere. As people were dying in the countryside, grain they had grown was sold abroad to fund the Soviet industrialization and modernization campaign.

This assault on the peasantry occurred in the context of a broader campaign of intimidation and arrests of Ukrainian intellectuals, writers, artists, religious leaders, and political cadres, who were seen as threats to Soviet state-building aspirations.

The Soviets went to great lengths to misinform and deny, desperate to conceal the truth about starvation in their country while promoting the Soviet Union as a socialist paradise. Soviet authorities refused offers of international aid, maintaining that there was no famine, and the famine remained a taboo topic within the Soviet Union.

It was brave and conscientious foreign witnesses who first reported on the Famine and its causes. These few journalists, unlike many of their colleagues, defied Soviet censorship at the cost of their journalistic privileges in the Soviet Union.

Notably, Canadian Rhea Clyman was likely the first journalist to report on the Famine, which she witnessed before her deportation on accusations of spreading “false news” about the Soviet Union. Detailed accounts of starvation were also published by Welshman Gareth Jones who circumvented restrictions on travel to famine-struck regions to witness the truth for himself.

Recent research reveals that already in the 1930s, Ukrainians in Canada and the US had mobilized to protest the Kremlin’s starvation of Ukraine. Diaspora press included reports drawn from eyewitness accounts and personal letters sent from the starving to relatives in North America, including from German and Jewish minorities in Soviet Ukraine. The letters included desperate pleas for help and requests for US currency that might offer a chance to buy bread for survival.

These and other efforts to raise awareness were largely ignored by the international community. It was fifty years later – in the 1980s – that Ukrainian communities in North America achieved success in bringing the famine to the public’s attention, and continue to do so through the collection of testimonies from Holodomor survivors; the production of documentaries and exhibits; the development of educational curricula; and through effective lobbying of governments to officially acknowledge the Holodomor’s occurrence and to recognize it as genocide.

The establishment of high-profile Ukraine research institutes at Harvard University and the University of Alberta also created a crucial forum for promoting research and awareness of the Holodomor. The publication of Robert Conquest’s Harvest of Sorrow in 1986 marked a watershed in the study of the famine, sparking debates in academic and political circles. Research on the famine gained further momentum with the fall of the Soviet Union when Soviet archives were opened. With Ukraine’s independence in 1991, research was invigorated in the homeland, and activists and scholars in Ukraine have cooperated with their counterparts abroad ever since.

Further strides were made possible with the establishment of the Holodomor Research and Education Consortium (HREC) in 2013 with the generous support of the Temerty Foundation, as a project of the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS), University of Alberta. HREC engages scholars and institutions across disciplines through conferences, grants competitions, fellowships, translation and publication programs, and education initiatives.

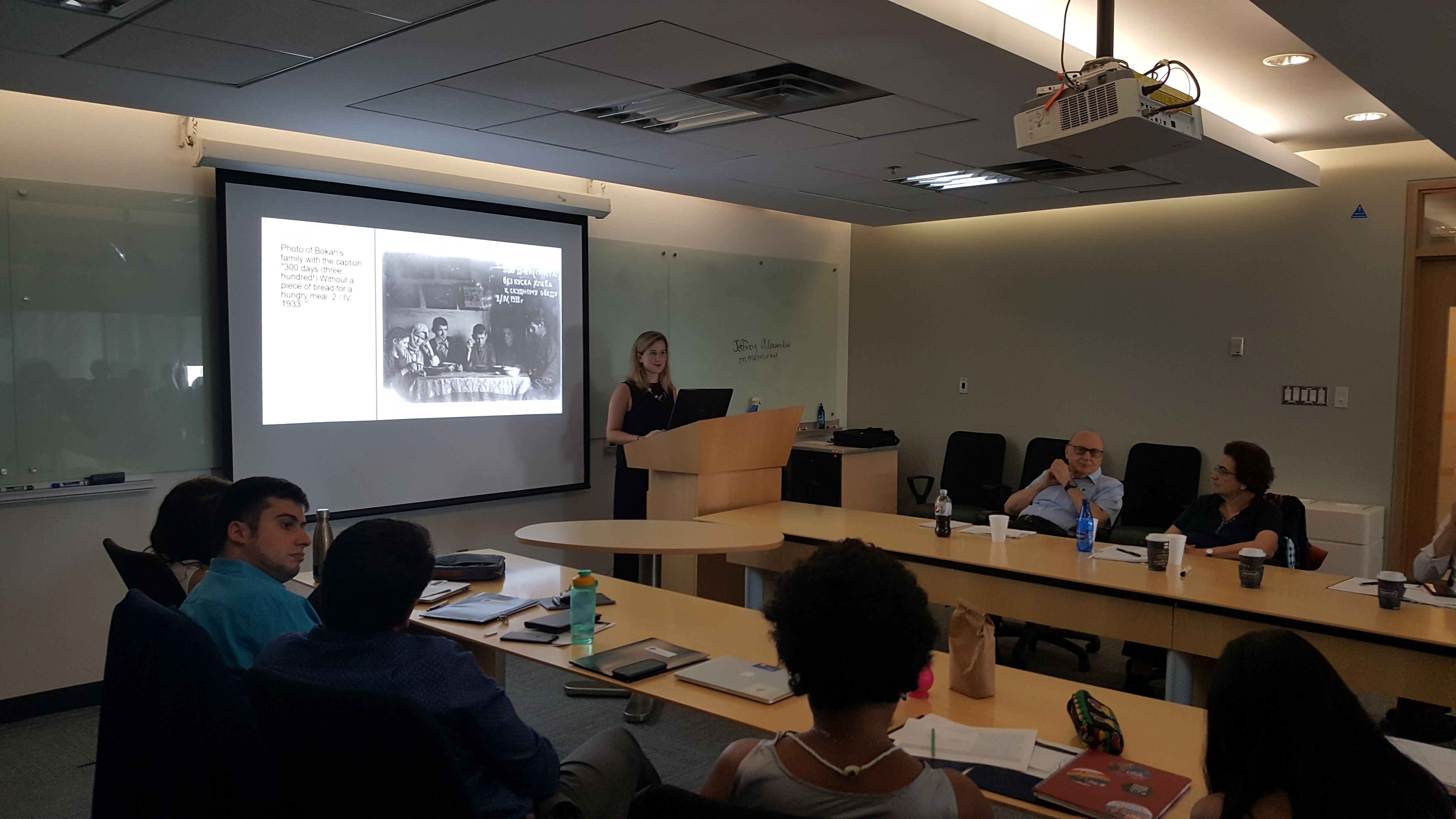

Among its many activities, HREC supports young scholars of the Holodomor and sponsors their participation in workshops and courses, including in the Genocide and Human Rights University Program, held by the International Institute for Genocide Studies (A Division of the Zoryan Institute).

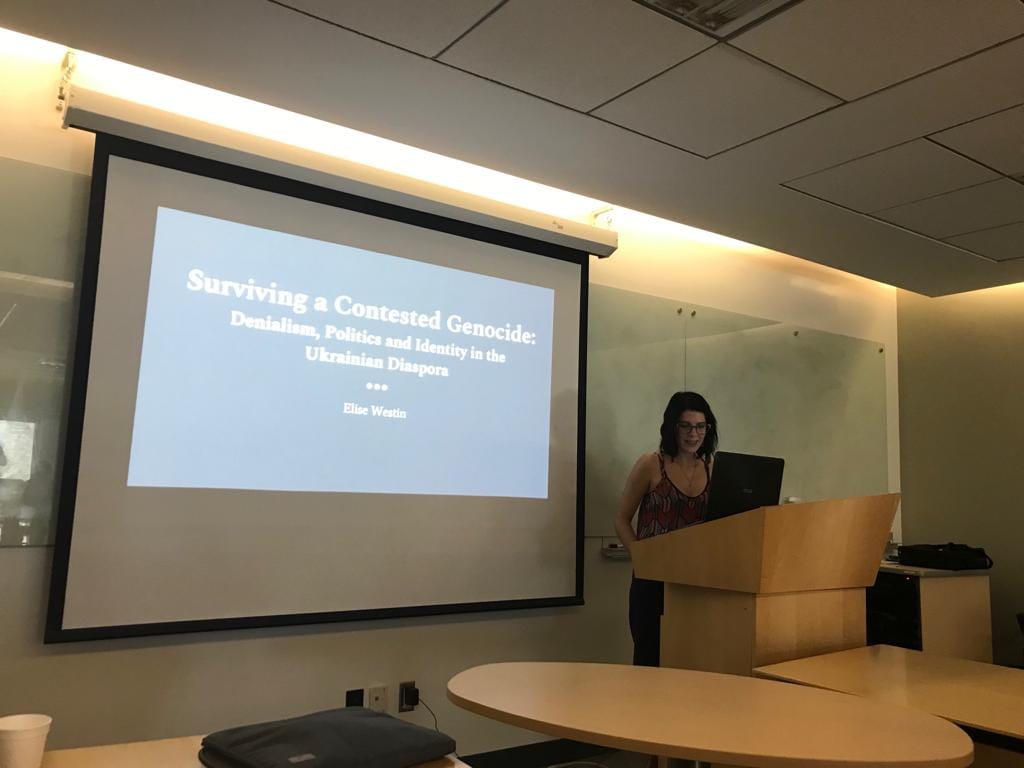

One scholarship recipient, Elise Westin, reflected on her participation in the course:

“While the program’s comparative approach to genocide studies highlighted a number of gaps in Holodomor research…it also pointed to ways in which the Holodomor was unique. Mass murders committed by attrition are among the least understood forms of genocide and can take much longer to gain recognition. By understanding how these forms emerge, I believe that we can identify them more readily and spare victims the pain of enduring the contested status that has followed many survivors of genocide.”

These developments in Holodomor research and advocacy cannot be taken for granted. There are still those who deny that the Holodomor occurred, that it was a man-made famine, or that it was an assault on the Ukrainian people. This worrisome reality is connected to issues in contemporary Ukraine and the denial, disinformation, and fake news surrounding Russian aggression in Crimea and the Donbas, where forces continue to manipulate history to fulfill territorial ambitions.

As we commemorate the 86th anniversary year of the Holodomor, we in the field of Holodomor studies recognize that we are part of a larger work-in-progress, which builds on decades of work and advocacy, draws on new insights and perspectives from comparative study, and continues to seek out new forums for discussion, all in pursuit of the following objectives: to inform the prevention of genocide, to expose and defend the truth, and to ensure that the Holodomor and its victims are never forgotten.

The Zoryan Institute and its subsidiary, the International Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies, is the first non-profit, international centre devoted to the research and documentation of contemporary issues with a focus on Genocide, Diaspora and Homeland.

11 Jul 2025

Academic Journal, Genocide Studies International, Expands its Reach with New Podcast Partnership

Read More

09 Jul 2025

“The Conduct and Response of ‘Third States’ to Gaza” with Jon Allen – Recording Now Available

Read More

03 Jul 2025

Open Letter On the Proposal to Rename the Armenia-Turkey Border Crossing After Talat Pasha

Read More

27 Jun 2025

The Zoryan Institute Releases Special Episode of Dispersion Podcast on Canadian Multiculturalism Day: “Friendship as Citizenship” with Dr. Rajesh Shukla

Read More