August 30, 2022: Today marks the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances (ED), a day to commemorate the disappeared, and to acknowledge the immense harm this heinous crime causes to their family, friends, and communities.

Enforced disappearance is a complex crime that involves the arrest, detention or abduction against one’s will by officials of different branches or levels of government, or by organized groups or private individuals acting on behalf of, or with the support, direct or indirect, consent or acquiescence of the government, followed by a refusal to disclose the fate or whereabouts of the persons concerned or a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of their liberty, which places such persons outside the protection of the law. As a result of the outcome of the “Velásquez Rodriguez Vs. Honduras” case in 1988, it is recognized that the crime persists as long as the fate or whereabouts of the victims remain unknown (paragraph 181). In the same judgment, the Court settled that, when committed in association with a policy of persecution or extermination such as the one in Guatemala, ED constitutes a crime against humanity.

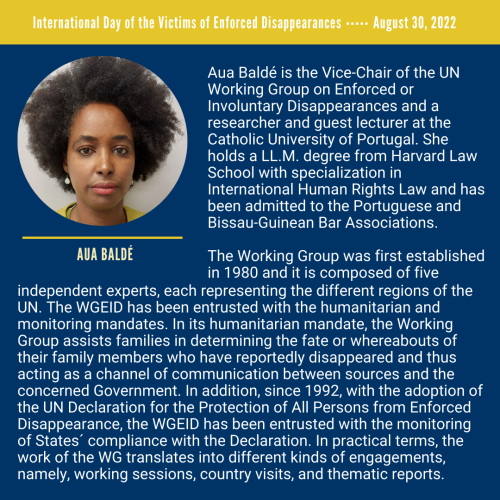

In anticipation of this important day, the Zoryan Institute had the privilege of interviewing two inspiring lawyers and graduates of this year’s GHRUP, Maria José Freire and Aua Baldé. Both Maria and Aua focus on this devastating crime in their work, and took the time to provide ZI with insights on the impacts this crime has on the rights of disappeared individuals and their families, the contexts in which ED is common, why perpetrators commit ED, and what international legal mechanisms exist to address this crime.

AB: Let me start here by underscoring that both the disappeared person and any individual who has suffered direct harm as a result of ED, such as family members, are considered victims. Bearing this in mind, it is important to understand that ED have a profound effect on the victims as well as the communities where they occur. A disappearance has a double paralysing effect on the disappeared person who is frequently tortured and in constant fear for their lives, and on their family, unaware of the fate of their loved ones, waiting, sometimes for years, for news that may never come. In addition to emotional distress, ED also have material consequences for the family. It is very common that the disappeared person is the breadwinner of the family and as such the disappearance has a financial effect, resulting in both economic and social marginalization. Furthermore, it is also important to further underline that, enforced disappearance has frequently been used as a strategy to spread terror within society and such the feeling of insecurity is not circumscribed to the those close to the disappeared but also affects the communities and society as a whole.

MJF: In addition to ED constituting an absolute denial of the dignity and humanity of the victim, and thus, a transversal violation of their human rights, every ED continuously damages the rights of the victims’ relatives to truth, justice, identity, mental health, among others human rights. To follow up on Aua’s point, according to Mario Benedetti (1983), a missing person is almost more detrimental for families than a dead person. In his words “The disappearance summons a dose, despite small, of hope, always followed by an atrocious despair, which the next day gives way to a new hope, which never gives up, and so on. The dead person dies only once, while the missing person dies every day”.

MJF: ED has been committed by numerous states over time. It has materialized as a policy to eliminate political opponents or activists, as individual crimes perpetrated by security forces or government officials, or worst of all, as a semi-secret and genocidal power technique utilized to destroy a group while terrorizing the population. ED is committed in both democratic and authoritarian environments, although its systematic implementation originated in authoritarian contexts.

International concern over ED was primarily a result of its methodical implementation by authoritarian governments that consolidated between 1960 and 1980 in Latin America. In the Cold War setting, elites’ economic, political, and social interests were fueled by hatred and mistrust towards socialists and communists. Due to this sociological context, state and company officials coordinated regionally to forcibly transfer victims and their children, categorized as “enemies”.

AB: It is very difficult to single out contexts under which ED occur as they vary and have evolved over time. While historically associated with military dictatorships in contexts such as Latin American, ED are a global phenomenon that goes far beyond a specific region. This is even more so, if one considers the fact that the Working Group has registered cases in over 100 countries in the world. ED occurs in conflict settings, and current trends include disappearances in contexts of counter-terrorism operations, including secret detestations, short-term disappearances, and extraterritorial abductions; disappearances in the context of migrations and disappearances committed by non-state actors.

AB: ED happen in contexts of prevailing impunity and disregard for the rule of law, including judicial guarantees. In addition to the effects on the disappeared person, the perpetrators of ED seek to intimidate the families and the community by instilling fear and spreading terror, and in doing so silence dissenting voices. As such, although ED are aimed at individuals, they are also often used as a strategy to control a group.

MJF: Prior to 1994, the “disappearance” provided an ideal setting for any repressive, authoritarian or genocidal government in order to conceal any signs of an international crime and thus guarantee impunity. Provided that ED wasn’t characterized by international treaties yet, what law could be applied to a person who went missing from day to day without ever resurfacing? Perpetrators took advantage of this loophole. The intent in this crime includes both removing the passive subject from the protection of the law and intimidating the civilian population. Argentinian perpetrator, Jorge Rafael Videla, said in a public interview (1979), “He is a disappeared person, he has no entity, he is neither dead nor alive, he is missing. We cannot do anything about that”.

MJF: Nowadays, all international systems of human rights have jurisdiction to take individual complaints for cases of enforced disappearance. Yet, as a consequence of the principles of complementarity and sovereignty, national courts have priority of jurisdiction. To this day, there are national legislations that impede the investigation of certain perpetrators or periods of history. Firstly, these states’ internal legal mechanisms must be aligned with the new paradigm of international human rights law and must attend to victims’ cases. Second, probing a system of systematic persecution surrounding the ED transforms this crime into imprescriptible. Thirdly, since all states are bound to combat ED impunity, universal jurisdiction could serve as an ideal legal mechanism for victims who find their national jurisdictions corrupted to seek justice, although it can (and has) created political tensions.

AB: Internationally speaking there is a significant array of protection mechanisms, with the Convention [for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance] being the last one. The Convention is the first universally legally binding document concerning ED with focus on prevention and punishment of ED, as well as on reparations and guarantees of its non-recurrence. It details State Parties obligations vis-à-vis the ED phenomenon and the corresponding victims´ rights. The Convention represents significant progress in international law, in particular by defining the non-derogable right not to be subjected to an enforced disappearance. It affirms that enforced disappearance constitutes a crime against humanity when practiced in a widespread or systematic manner. One of its major innovations is article 24 which expands on the definition of victims to include not only the disappeared person but also any individual who has suffered harm as the direct result of an enforced disappearance, including family members. The Convention also has provisions on the right to obtain reparations which covers both material and moral damages. However, despite the existence of a universally legal binding document on this issue, the level of ratification remains

AB: Denial is an essential element of the definition of enforced disappearance. In fact, the disappearance itself is followed by the concealment of one’s fate or whereabouts and/or the refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty. Therefore, it is crucial to document cases of ED before mechanisms such as the Working Group, not only as a way of keeping the record straight but also as means to call on the responsibility of the concerned State.

MJF: In my view, one of the most serious crimes committed against humanity is ED, not only for the tortures the victim is subjected to, but for its purpose of hindering justice and denying the truth by abusing the power of the State. Denial, according to Daniel Feierstein, is a phase of genocidal processes. It’s a social genocidal practice in the sphere of “symbolic representation”, which refers to how post-genocide societies present and recount such traumatic events. The act of denial damages the victim’s memory, thereby impairing the right of their relatives and their community to remember. Acknowledging that the right to the truth regarding human rights violations is now widely recognized in international law, denying ED as part of a widespread policy obviously causes harm and revictimization. Hence, it may result in criminal prosecution.

AB: There are several coping mechanisms, but my family and friends are very important in this process. Having a very small but reliable group of people with whom one can decompress with and focus on other issues is fundamental for re-shifting ones´ gear and attention to other issues. In addition, practicing pilates has also been very helpful for my physical help. I am currently in my hometown in Canchungo, Guinea-Bissau Gmapros. This is not something that I can do as often as I would like, but being here always provides a safe environment, where I can fully disconnect and re-energize. Finally, the fact that I am also a mother to a seven years old girl, and to have the privilege to see her grow, is also something that provides me with both the strength to continue on this path, as well as hope for a brighter future.