May 28, 2020 – Toronto: Today is the 102nd anniversary of the independence of the Republic of Armenia. On a day like today, one contemplates the importance and meaning of statehood, sovereignty, independence and national identity for people worldwide.

What can one glean from a study of statehood and its potential impact on security, sustainability, culture, language, and identity? Does the independence of a recognized nation-state provide sovereignty to its people? Is independence important or absolutely necessary for people seeking self-determination?

In order to understand these issues, we explore the role of statehood, independence and sovereignty in cultivating a collective national identity using four unique examples: The First Republic of Armenia, The Republic of Ireland, Indigenous Peoples of Canada and the Kurds.

We first look at the First Republic of Armenia and the Republic of Ireland, whose distinct and traditional cultures were given new leases on life after statehood and independence.

THE FIRST REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA

The formation of an independent state in 1918 was absolutely essential for the self-preservation and regeneration of the population. Armenians had suffered unimaginable violence and persecutions through the 1915-1916 Armenian Genocide, which resulted in the near decimation of the Western Armenian population. This pushed them to strive for statehood and a collective future for their people.

The formation of an independent state in 1918 was absolutely essential for the self-preservation and regeneration of the population. Armenians had suffered unimaginable violence and persecutions through the 1915-1916 Armenian Genocide, which resulted in the near decimation of the Western Armenian population. This pushed them to strive for statehood and a collective future for their people.

Although the First Republic was the first political entity for Armenians in over 500 years, Armenians had centuries of rich history, culture, science, and literature to preserve and protect. Political leaders of the newly established independent state put a strong focus on the formation of a national ideology, values, preservation of traditions and the centrality of the Church as a protector of Armenian religion, language, culture and identity. The government also placed a heavy emphasis on the unity of the Armenian people. This is done not only through the creation of a judicial system, a national currency, flag, anthem and a Coat of Arms, but through the 1919 Declaration of a Free, Independent and United Armenia, as the government also proclaimed itself the government of Western Armenia, the lost homeland.

While the First Republic only lasted a total of 32 months, it remains, in many ways, a symbol of a great national achievement for the Armenian people and their statehood. The modern Republic of Armenia regained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 through a national referendum.

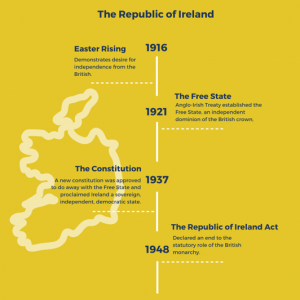

THE REPUBLIC OF IRELAND

The Republic of Ireland, like the First Republic of Armenia, achieved its independence and statehood in 1922 after years of revolutionary struggle.

The Republic of Ireland, like the First Republic of Armenia, achieved its independence and statehood in 1922 after years of revolutionary struggle.

Statehood, for the Republic of Ireland, has meant the reconvening and reconciling of a collective identity. Language represents an important aspect of this collective identity and as T.J. Ó Ceallaigh and Áine Ní Dhonnabháin argue,

“Since the foundation of the Irish Free State, the education system has been targeted as an agency and model for Irish language planning, education and language revitalisation and has had a critical role in generating linguistic ability in the Irish language.”

Similar to Armenia, Irish independence fostered a move towards the unity of the people and the preservation of a collective identity in which the resurrection of traditional language, culture, and religious tradition played important roles. In both cases, statehood and independence were critical in protecting and enriching the culture of these distinct nations.

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES OF CANADA

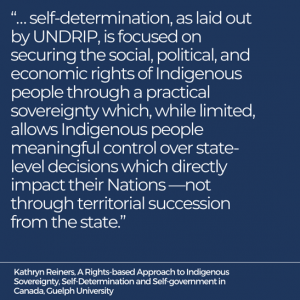

Whereas statehood is the status of being a recognized and independent nation within a restricted geographical area, sovereignty refers to the condition of political independence and self-government. For the Indigenous Peoples of Canada, sovereignty is established by: a) Aboriginal rights, b) the existence on and use of the land prior to contact with Europeans, c) what the 1982 Constitutional Act calls “Aboriginal title”, which manifests through treaties and alliance-making with other nations.

Whereas statehood is the status of being a recognized and independent nation within a restricted geographical area, sovereignty refers to the condition of political independence and self-government. For the Indigenous Peoples of Canada, sovereignty is established by: a) Aboriginal rights, b) the existence on and use of the land prior to contact with Europeans, c) what the 1982 Constitutional Act calls “Aboriginal title”, which manifests through treaties and alliance-making with other nations.

Practical sovereignty calls for a delegation of power from Canada’s provincial and federal governments. Therefore, in theory, with treaties signed, practical sovereignty would give Indigenous nations control over matters that directly influence them, resulting in collective rights to determine land and water-use, decision-making power for economic development, and establishing services that seek to revive and protect collective identities and Indigenous language and culture. However, a limitation of practicing Indigenous sovereignty in Canada is that it operates within a rigid legal and political framework of the Canadian nation-state. This leads to questions of how flexible Canada can be in meeting the unique needs of Indigenous sovereignty.

THE KURDS

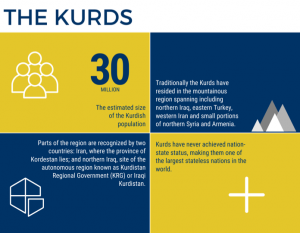

For the Kurds, an ethnically distinct group who have traditionally inhabited a mountainous region straddling the borders of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran, and Armenia, independent statehood has been sought for centuries but not attained.

For the Kurds, an ethnically distinct group who have traditionally inhabited a mountainous region straddling the borders of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran, and Armenia, independent statehood has been sought for centuries but not attained.

At the beginning of the 20th century Kurds began to plan for the formation of a homeland state recognized by the Treaty of Sèvres, but these hopes were soon thwarted.

In September 2017, with overwhelming support (over 93% of votes cast in favour) Iraqi Kurdistan voted for independence. The legality of the referendum was rejected by the Federal government of Iraq. This was in part due to the major role that geopolitical factors play, as Azad Berwari & Thomas Ambrosio argue, “The rejection of Kurdish independence by Iraqi Arabs, outside countries, and the UN illustrates that the full expression of Kurdish national identity remains subject to the policies and interests of others.” The referendum led to military conflict with the Iraqi central government. As a result, the Kurdish regional government lost 40% of its territory, including the Kirkuk Oil Fields, which was its main source of revenue.

One look at recent history shows how the forces of geopolitics act against the aspirations of the Kurdish people for statehood. A vivid example was Washington’s decision to abandon them and side with Turkey as it invaded Northern Iraq and Northern Syria, a territory heavily populated by Kurds, and where the Kurds were the main allies of Washington in bringing the ferocious war against ISIS to a successful conclusion.

In comparing the four cases above, we see the effects that statehood, sovereignty, and independence, respectively have on cultivating a collective national identity. For some, such as Armenia and Ireland, becoming a nation-state enabled self-preservation after histories of violence and oppression and the revival of traditional language, culture, and religion. Whereas for the Indigenous Peoples of Canada, preserving collective national identities means establishing practical sovereignty within a state. For the Kurds, 30 million strong, recognized statehood would represent an opportunity to develop as a political entity, as much as a cultural one, in a defined territory, with a government that will have the capacity to enter into relationships with other states.