August 3, 2021: Today marks seven years since the genocide against the Yazidi community in Sinjar, Iraq. On this day of commemoration, the Zoryan Institute invites you to learn more about the genocide and the many ways in which the Yazidi community is still vulnerable and in need of international support and recognition.

Genocide is a shared human experience and as such, must be the concern of all individuals and institutions. The study of genocide and forms of genocidal violence is critical to the prevention of future genocides.

Seven years on from the attack against the Yazidi community of Sinjar, and there remains a lot to learn from this case, and much to be done to support the Yazidi community. To this end, the Institute had the opportunity to speak to three individuals actively working with the Yazidi community who share their insights on the importance of international recognition of the genocide, the impact of the Yazidi Survivors Law and efforts to rebuild the Yazidi homeland.

Read this piece in Armenian.

In the middle of the night on August 3, 2014, ISIS forces launched an attack on the Yazidi community in Iraq. Iraqi forces stationed in Tal Afar (Northwestern Iraq) departed two weeks after ISIS took control of Mosul. For a full eight days, the region was besieged. Those who were not able to flee in their vehicles attempted on foot across the mountains.

The IS advance throughout the Yazidi heartland of Sinjar, Northern Iraq, led to massive displacement of the Yazidi people. An estimated 400,000 Yazidis became internally displaced peoples (“IDP”) residing in camps in Northern Iraq, with roughly 7,000 estimated to be enslaved by the Islamic State, and many missing, unaccounted for or presumed to be seeking asylum in neighbouring states. Whilst the active assaults by the IS have ceased, the situation for the Yazidis remains dire.

Findings by the United Nations found that IS had committed extermination, murder, rape, torture, enslavement, persecution and other war crimes and crimes against humanity, against the Yazidis. Recently, the head of the UN investigatory team, lawyer Karim Khan, stated that they found “clear and convincing evidence that the crimes against the Yazidi people clearly constituted genocide”.

Q: Güley, Conflict-related sexual violence was particularly widespread during the Yazidi genocide. How important is it for those who study genocide/genocide prevention to take into account the role that gender played in the perpetration of this genocide?

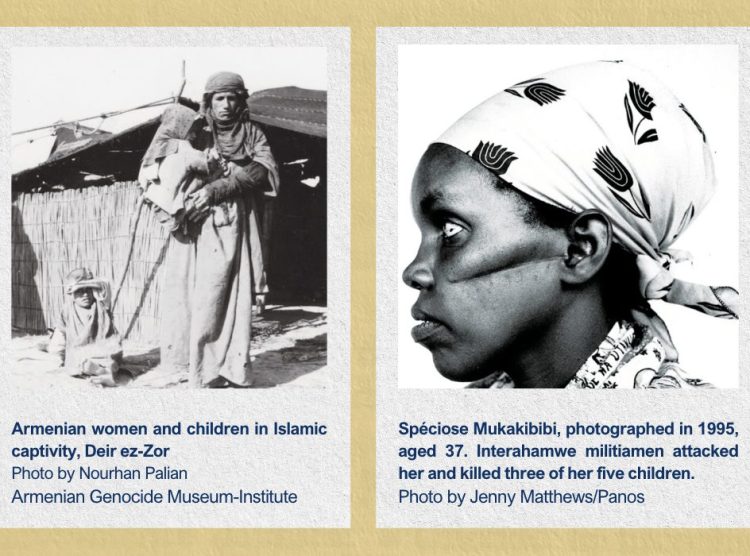

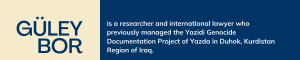

A: Genocide is not committed only through mass killings. A gendered analysis of genocide reveals a complete picture of how the intent to destroy a group is carried out through violations that target specific genders. Executing a systematic genocidal campaign against the Yazidi community, the so-called Islamic State killed men and older women, forcibly recruited boys, and sexually enslaved women and girls, pointing to the role played by gender and age, in addition to religion.

These violations did not occur in a vacuum; they are rooted in inequalities that pre-date the genocide. Yazidis’ history of persecution and structural gender inequality underlies IS’s use of sexual violence as a means of genocide, which is reflected in its ideology that imposes strict gender and religious norms. To deliver the promise of “never again”, these historical injustices must be addressed.

Q: Iraq recently adopted the Yazidi Survivors Law (YSL), which recognizes the Yazidi Genocide and promises reparations to survivors. Why is this law important and what are the next steps?

A: The YSL, adopted by the Iraqi Parliament in March 2021, provides for compensation, land or housing, medical and mental health services, return to study, and employment to Yazidi survivors of captivity, sexual violence and mass killings. It also officially recognizes the Yazidi Genocide and declares August 3 a national day, on which the genocide shall be commemorated. This law is important because of the wide range of benefits it promises that can redress some of the grave harms caused by IS violations, which are worsened with seven years of very little response by Iraq. The YSL also holds symbolic value as it acknowledges the suffering of the Yazidi people, and women in particular.

The adoption of this law would not have happened if it weren’t for the tireless advocacy by Yazidi survivors, as well as civil society organizations. It is truly remarkable how swiftly and successfully the survivors, the community and civil society mobilized for the YSL, which directly influenced lawmakers in introducing certain amendments to the law’s final text in line with survivor demands.

What follows the adoption of the YSL is perhaps the most challenging phase: implementation. Given how late Iraq was to adopt the YSL, it must urgently take necessary steps to ensure benefits reach survivors. Crucially, however, Iraq must address the lack of security, infrastructure and services in Sinjar for voluntary and dignified returns, considering that the majority of Yazidis in Iraq are displaced, living in camps since the genocide. Moreover, perpetrators must be held accountable through fair trials that recognize the gravity of the IS crimes against the Yazidi.

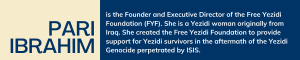

Q: Pari, what are some of the obstacles for recognition of the August 3, 2014 attacks on Sinjar as genocide? How might recognition of this genocide help the survivors of this crime? How might it help prevent future atrocities?

A: The major obstacle that stops recognition of the Yezidi Genocide is apathy, just like with other mass atrocities. However, we as Yezidis should also note the progress that has been made. I am a citizen of the Netherlands, and many of us have pushed for years to see our Parliament recognize the Yezidi Genocide. This just happened in July 2021, nearly seven years later. But it happened. Now there are many parliaments that have recognized the genocide, including Belgium, also in July. In our case, lack of evidence or absence of ‘intent’ is not the problem. ISIS argued and demonstrated its explicit intent to eradicate Yezidis as a goal in itself, and then carried out actions to accomplish their goal. It may be that some countries are hesitant to recognize genocide because they fear there may be actions they are obliged to take next, so they prefer to look away. This is the apathy that allows mass atrocities to occur, not only against Yezidis but in other places around the world too.

Recognition is important to individual survivors and the entire survivor community. It is not sufficient, but it is a requisite first step. If we cannot even acknowledge what has happened, there is no realistic prospect of addressing the crimes, the damage to victims, the pursuit of justice, the need for reparations, the requirements for recovery, and other related matters. In a domestic setting, one cannot address the impact of a crime if the crime itself is not recognized.

Recognition of genocide does not all by itself prevent future atrocities. ISIS is currently regrouping and its goals are not different from 2014, both in terms of the Yezidi population and their general efforts to destroy life and freedom in Syria and Iraq. But recognizing genocide does accomplish some things that can lead to preventing future atrocities. By publicly creating a clear record of what happened, it is much more difficult to ignore the actions of the past. This affects those who are neither Yezidi nor ISIS, but may be citizens in places in Syria or Iraq or just citizens around the world. And as mentioned, it is the first step in a number of steps to combat impunity for perpetrators of crimes. It is not sufficient, but it can lead down the path to something that could be sufficient. If those who led these atrocities and those who participated in them face justice and accountability, which requires an initial acknowledgement and recognition of the crimes, this would go some length in preventing future atrocities. In the opposite way, impunity fuels further atrocities. Yezidis have suffered 74 genocidal attacks. This needs to be the last one.

Q: What impact has the genocide had on communal cohesion and tradition? How does impunity further this destruction?

A: The Yezidi Genocide of 2014 has had a devastating impact on the community. Every family has been affected. I do not believe cohesion or tradition are the main victims of this genocide. Actually, it is the individual families. Yezidi traditions have existed through many attacks and will continue. This can be rebuilt. But those lives that we lost can never be replaced. The women and girls who were raped and literally enslaved will have to do the hard and painful work of recovering psychologically and physically. The crimes cannot be undone. I do not worry for traditions, I worry for the individuals who suffered the crimes. In this sense, impunity for the perpetrators is a terrible dishonor to those who were killed, whose bodies were left to the dogs in the fields around Sinjar. And it is a continuous source of pain to the family members of the deceased. Separately and just as painfully, individual Yezidi women must carry on, knowing that those who raped and enslaved them are in many cases walking free. This is one reason why justice, though incredibly difficult, expensive, and detailed, must be done. It cannot be ignored because it is hard.

Q: To this day, over 2500 Yazidis are still missing, mainly the younger single women and the young boys. What efforts are currently in place to find these missing people and how should the international community be supporting such efforts?

A: It is an outrage and an abomination that seven years after a genocide, nearly three thousand civilians should still be unaccounted for. FYF has raised this as our number one point in the 3 August 2021 statement and series of recommendations. To be realistic, we know that very sadly a percentage of this number represents those who were killed by ISIS or those who committed suicide in captivity. So we know that some are never coming back. At the same time, we know that some are still alive, held by ISIS members or accomplices in places like Syria, Turkey, or Iraq. Tracking down the missing is a very difficult job. Intelligence is required. We are calling on the Global Coalition to Defeat Daesh, Interpol, and services in Europe, Iraq, and NE Syria to establish a serious plan to rescue those who are alive and identify the remains of those we have lost. We as Yezidis do understand that this is not an easy task. But we know that intelligence services are tracking the communications and actions of ISIS members and their associates. We would like the issue of the missing Yezidis to be a real priority during intelligence and counter-terrorism operations in Iraq and Syria.

Q: Olivia, mass grave sites have recently been found and excavated (as recently as 2021), but over 2500 Yazidis are still missing after the 2014 genocide. Are there efforts in place to locate and identify these missing persons?

A: Unfortunately, to date, there have been no coordinated efforts to search for and rescue the 2,800 Yazidis still missing. As Nadia Murad has publicly stated for years, this is a failure of both the Iraqi government and international community. These women and children feel they have been abandoned, and in many ways they have. The horrors of 2014 never ended for them and they deserve our support to both escape captivity and rebuild their lives. While a few individuals have undertaken rescues over the years, these have yielded minimal results because the individuals do not have the same capacity for rescue as a government or coalition of governments would. The NI programs team is thinking strategically about how to address this issue given the lack of political will exhibited by the GOI, KRG, or other nation states/international organizations working in the region. We hope to be able to show these women they have not been forgotten and encourage the international community to do so as well.

Q:What efforts are underway by Nadia’s Initiative to rebuild the Yazidi ancestral homeland of Sinjar, Iraq?

A: NI has been working on the ground in Sinjar, Iraq since 2019 when we began building out our programmatic work in the region. In the past 2 1/2 years, we have implemented dozens of projects in Sinjar. Our work is focused on restoring education, healthcare, clean water, and livelihoods. We are also focused on cultural preservation and women’s empowerment. You can see the full scope of our programmatic work here. While we implement some of our projects directly, we also partner with INGOs and local NGOs. It is critical that our programming is informed by the communities we serve, which is why a section of our staff is dedicated to regular community outreach workshops through focus group discussions and surveys, which help to ensure the design and development of our programs is in line with community needs.

Q: Yazidi communities have experienced immense trauma and suffering. Women and girls were taken captive and raped. Young men and boys were killed or sent to jihadi training, mostly in Syria, to follow ISIS fighters. How has the trauma of the survivors been addressed? Does Nadia’s Initiative have therapists and support workers working directly with the survivors?

A: Many INGOs and NGOs operating in the region of Northern Iraq take a reductionist approach to the mental health needs of survivors. This means they implement programming that focuses solely on provision of MHPSS services. While mental health care is critical to trauma recovery for survivors, it is not enough on its own. NI has heard from many survivors who expressed their frustrations with organizations that provide only MHPSS support or vocational trainings. For survivors who go to therapy sessions or trainings, they often return home to their tents or dilapidated houses with no clean water, no job opportunities, and no way to ensure their children receive a proper education. That’s why NI centers the holistic needs of survivors in our programming in Sinjar. This means that all our programs take into consideration the varying and individualistic needs of survivors, which enables us to develop projects that provide survivors with a range of support — including MHPSS, livelihoods, education, healthcare, shelter, and clean water. We are now in the second round of a project that is establishing small businesses for survivors and women in Sinjar. Women who have benefitted from this empowerment program tell us that having their own business helps them immensely with their trauma because they now have something they can be proud of and focus their energy on. An additional problem related to mental health in Northern Iraq is a severe lack of qualified therapists in the region. NI is fortunate to have a clinical psychologist and case workers from Sinjar on our protection team. But, in many cases, organizations will hire expats to come into Northern Iraq and train local staff for a few weeks or a month and then write in their reports that there is now a therapist working for the organization. As you can imagine, this can be dangerously re-traumatizing when survivors are exposed to individuals who do not have the academic or work background to be providing therapy or subscribing medication.

By studying and encouraging dialogue on cases such as the Yazidi genocide, the Institute believes it can contribute to the common body of knowledge surrounding genocide and mass atrocities. This common body of knowledge allows for the truth to be centered, and the voices of those who experienced genocide and gross human rights violations to be heard.

To this end, Zoryan Institute publishes two academic journals, supports multi-disciplinary research, documentation, lectures, seminars, colloquia, and publications and hosts its annual Genocide & Human Rights University Program to educate the next generation of genocide scholars.

For almost 40 years the Zoryan Institute has served the cause of scholarship and public awareness relating to issues of universal human rights, genocide, and diaspora-homeland relations, for more information on our work explore the “About Us” and “Our Work” tabs above.